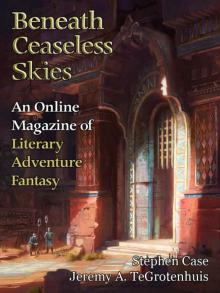

- Home

- Stephen Case

Beneath Ceaseless Skies #212 Page 2

Beneath Ceaseless Skies #212 Read online

Page 2

The wizard spoke a word, and the fire in the central bier of the ship flared. The canvas of the bladder above us flapped, and we rose higher.

The wizard saw my gaze rise as well.

“Primitive,” he said, gesturing toward the gas bladder. “I explain this to my brother. Less efficient than the aeroliths.”

I said nothing.

“Tell me what they are like,” the wizard ordered.

“What?”

“The aeroliths in your valley. How are they discovered? How are they mined?”

“Don’t you know?” I asked.

Only days ago, when we had arrived at the Capital, I would have been horrified to imagine speaking to one of the Emperor’s family in such tones.

His eyes left mine and scanned the clouds we rode among. “I leave Cor Capitulus only by air. I know little of the lands beyond.”

“There are clues,” I explained begrudingly. I had often scouted our hills and gullies for the stones. “You can recognize a seam, sometimes, if it’s not too deep, by the way the stones lie. They tilt at unnatural angles. Sometimes they’re tethered to the ground by only a slender neck of natural stone.”

He nodded.

“We make scrapings,” I went on, still sullen but warming to the memories. “If they drift on the wind, you know you’ve struck near a true aerolith. We—my brothers and my father—will drill a stay into it, and then they’ll dig it free.”

We were moving so fast the clouds passed us only slowly, rearing and breaking like horses of foam.

“Do you know why the aeroliths are found only in the valleys,” he asked, “and not on the plains or near Cor Capitulus?”

I nodded again. “My grandmother told me stories. Legends.”

He pulled the tiller, lowering a gossamer sweep that caught the wind and turned us in a broad rising arch toward an approaching wall of clouds, the thunderheads I had seen earlier.

“Legends,” he said, “are only deep history.” He was a wizard, so his words were clear and audible, even in the howling of the wind, even when almost whispered.

We flew on in silence.

The wall of clouds reared higher, like a cliff of broken white, the sun lost behind it. The wind, which we had ridden on earlier, was now cold and biting as we turned into it.

I had never seen clouds like this. I had seen them from the ground and wondered what it must like to be among them. But here were mountains of cloud, growing and shifting, that dwarfed any mountain below.

“This is the cloud-wall,” the wizard said. “Hold the sweeps steady.”

He pushed the tiller into my hands and walked to the prow. By now the clouds were so close I had lost all sense of scale. It was as though we were approaching a wall of fog.

I heard the word the wizard spoke, but I did not understand it. The force of it crackled in the air around us, hanging for a moment like a curtain, and then the clouds responded. A long shaft opened in the white wall. The ship slipped along it, and the clouds reared up on either side as though we sailed a narrow canyon.

“There are faces!” I shouted.

There were visages in the clouds. Or they were the clouds. They were watching as we passed, but they seemed to fall away, dissolving into cloudscape, as soon as I noticed.

I thought again of my grandmother’s stories of the sky-giants.

“They are anima,” the wizard said. “Spirits of the air. They are tethered here as guardians.”

“They’re angry,” I said.

“They are jealous.”

Soon we were past the broiling walls of white and into a hollow open to the sky but still surrounded by clouds. At its center floated a structure of stone. The boat lifted closer, and I saw that it was a narrow tower set on a carved platform of pale stones.

“The aeroliths,” I breathed.

He nodded.

There were men working on the outside of the structure. As we approached I could see they were stonecarvers, shaping the exterior with chisels and hammers.

“The winds surrounding my house,” the wizard said as we approached it, “are treacherous. You must know not only the word to part the cloud-walls but also the pathway through the labyrinth of wind that surrounds it.”

He was telling me there was no escape.

When the ship was close enough, the wizard gestured and a silver rope snaked from the vessel and tied itself to the edge of the stone platform. Stepping off the ship was like stepping onto firm ground.

The house hung solid and heavy in the sky.

I had arrived at my prison.

* * *

When we entered the house, I gasped. My eyes followed the circular line of the wall, but instead of the sloping ceiling of the tower above, I saw layer upon layer of balconies rising upward to be lost in a grey haze of distance. The wizard glanced at me before brushing past.

“It is a house of borrowed space,” he said over his shoulder.

There were workers on the inside of the house as well, doing a hundred tasks I couldn’t follow. The tower was a single round room, perhaps a quarter as large as the Blue Hall had been, with stairs running at staggered intervals to the balconies above. A huge circular table was in the middle of the floor, and the wizard walked to this now. A woman, bent and ancient, hovered over a mountain of gears and springs on the table’s surface.

“Will it be ready?” the wizard asked. “It must be the greatest you have ever constructed.”

The woman clucked her tongue and barely glanced up. “It will be everything I have ever constructed.”

Her voice was thick. I heard within it the blow of hammers in caverns far beneath the earth and somehow also the motion of branches in wind.

She met my eyes and smiled.

I followed the wizard to chairs and a cold fireplace at edge of the wide room. There was a tray with a kettle and a few pewter cups, all empty. The wizard took one, stared into it for a moment, and then sipped absently.

“How many gods are there?” he asked me.

My attention was still wandering the interior of the house, continually straying toward the room’s apex, where the rows of balconies stretched away in endless vantage. The staircases connecting each level were tight spirals of carved iron that drew the eye upwards and inwards like the shell of a nautilus.

“I don’t know,” I answered absently.

He set the cup back down on the tray with enough force to startle me. “How many?” he demanded. “What is the name worshipped in your village in the mountains?”

I thought for a moment, confused by his questioning. Father had an old and faded portrait of the Emperor in our lodge, and he would occasionally light a spiral of incense before it. He taught my brothers and me words to say that might have been a prayer. But my mother’s people—the people of the mountains—had a small shrine on the highest peak with a white stone they said was a tooth of the Walker.

I mentioned both to the wizard.

“So it is in all places.” The wizard took his cup again and sipped from it. Steam was rising from it now. “We have as many gods as we have villages, as many pantheons as we have languages. It is inefficient.”

I waited.

“My brother—the Emperor—will never rule a house so divided. Even now the Barons of the south believe they can carve the Shallows into their own holdings.”

He put the cup back on the tray.

“Why am I telling you this?”

I blinked. He was staring at me, waiting for an answer. I could hear workmen calling to each other far above. “I don’t know,” I said again. I looked around the house. “Because I will live here.”

He nodded. “Because you will serve me here.”

“But you haven’t explained anything.”

“One black cloud,” he whispered. “On the horizon. A single black cloud has escaped my weave of molding spells. As below, so it must be above: unity under dominion. Snare it for me. Bring it to heel. That is your test.”

“Why?” I asked

.

His smile was empty. “Because you are of the blood.”

Even as he spoke, his image wavered and fell to smoke. I heard movement at the doorway, but by the time I reached it he was gone, his form a figure on his departing air-ship already being swallowed by distance.

He was a wizard. He had left me, had slipped away, while I thought I still spoke with him.

Around me I heard the continuous sound of workmen chipping and shaping stone and the muttering of the woman bent over her mound of springs and gears, but I was alone in the house.

* * *

I did not know how to catch a cloud. I was imprisoned in a sliver of stone, which was itself cocooned within a hollow of clouds. From the windows of the house I could not even look down on the landscape below, hoping for a glimpse of the valley of my family.

The winds were stagnant and weak.

“You are of the blood,” the old woman said, echoing the wizard. Workmen continued to hammer at the stones of the house, and the balcony upon balcony arched up in an impossible dome over my head, but my mind was a blank.

I watched the old woman work, twisting together braids of copper sheeting and gears. Gear seemed to fit inside gear with the impossible geometry of the house itself.

“Because my father is a patrician,” I muttered. “I am a valuable hostage.”

“Not your father’s blood,” the woman clucked, and a spring within the pile of gears before her clicked in sympathy. “Your mother. You are the wind.”

My grandmother had been able to blow out a fire by flexing her fingers. It had been a trick to impress children, a tiny bit of imprinted magic, nothing more.

There was a candle burning beside her as the woman worked at the clock. I waved at it, but nothing happened.

The old woman smiled.

Something groaned inside the unborn timepiece before her, and the woman sighed. “The black cloud. Come.”

We climbed several sets of stairs, passing men pulling trunks or shelves from places I couldn’t quite see, polishing cabinets, and unpacking crates. None of the men would meet my eyes. They kept their heads bowed and whispered polite words as we passed.

When we reached the upper reaches of the wizard’s house (though there were still balconies fading to haze above), the woman stopped before a wide window that looked out into the boiling white clouds.

“There.” She pointed.

The sun filtered through a thin cap of cirrus above the bowl of clouds the house hung within. It felt as though the house floated in the midst of a chapel of white ivory.

Even as we watched, something passed over the sun and cast the tiny shadow on the wall of cloud before us. I craned my neck and saw a piece of cumulus, thick with rain and shadow, passing haphazardly along the slope of white.

“You must bring it to heel,” the old woman clockmaker said. “It irks the wizard.” She grinned as though we shared a secret. “His hold on the winds is not complete.”

I watched the cloud until it had disappeared from view. Part of me went with it, angry and rebellious.

* * *

I glance up from the scroll. Clouds have risen around the wizard’s house like mist, and I hear the faint patter of rain come from somewhere far overhead.

The timepiece ticks softly beside the door, its concentric rings gleaming like coins in the firelight. This was the clock that foretold the wizard’s fate, and it still speaks occasionally, though almost always in riddles.

“Who fashioned you?” I ask it.

It chuckles with the sliding of gears.

Something in her account troubles me. The wizard she describes is not the wizard as I recall. He was distant and sometimes harsh, but he was not cruel. He was not so hungry for power.

Time changes things, perhaps, but the wizard kept himself out of the step of time.

No, it is more than that. I feel like I am reading in a mirror, as though something has been reversed.

Sylva’s script changes here, growing more hurried, the ink carried across the page as though the strokes are reeds bending in a gale.

* * *

I don’t know how to catch a cloud. The wizard grows impatient. He comes to the house in the evenings, bringing orders for the workman and words for the old woman who labors over what is becoming in her hands an infant timepiece. It chirps at her fingers and on occasion whispers.

“You have knowledge of the winds in your veins,” the wizard tells me, but I shake my head. Though I am his prisoner, I will not play his games. My father was right to fear bringing me to Cor Capitulus.

“Indeed he was,” the wizard says.

The old woman chuckles.

“Let me go home.”

“I cannot.”

“He hungers for sight,” the old woman says later. Springs shudder under her fingers. “He has been promised vision by his brother.”

“Vision?”

“His eyes are weak. The Emperor has promised him new vision. Seeing stones.”

“What do they want?” I ask her. I am thinking of the wizard and his twin.

Gears groan and her knuckles crack. “Power,” she says. “The Barons of the south in their wind-ships test the Emperor’s authority. He cannot exercise dominion. He will send his brother when this weapon is completed.”

I stare at the labyrinth of metal at her fingertips. “What are you doing?”

She smiles. It is night, and the candles that line the table make the metal before her gleam like embers. “Giving birth,” she says.

I shake my head. This is house of riddles. Outside the windows there is only blackness. The house—my cage—is itself still enclosed in cloud.

“A single cloud,” the wizard orders again the next morning. He has come to his house early. His tea service is blue silver, and the steam from the cups this morning is thick, wreathing his head. “A single cloud, and you shall have your reward.”

“My freedom?”

He shakes his head. “You will serve me.”

My anger is hot and sudden. The tea, when I throw it toward his face, congeals in the air between us. He watches it without flinching. In another moment it rains down into the kettle.

“You cannot compel me,” I say, though my voice is soft. I would make it harder, but there seems no point.

“He would take you for a wife,” the old woman says later. The clock has now taken form on the table before her.

“My father was right.”

She nods. “He was. You have both royal blood and the wild wind-blood of the hills. Blood touched by Aeolius.”

“I’ll throw myself from a window,” I tell her.

The woman bites her lips for a time, as though wondering what effect this would have. Here in this house of dreams, where days run together like clouds meeting in a wind, even such a finalizing action would not perhaps have the intended consequence.

“He would catch you, I think,” the woman finally says.

She looks older. She has aged these past days. Her fingers tremble over the metal face of the timepiece she has fashioned.

“What time is it?” I ask her.

She looks down at it. “Now.”

The clock has figures I do not recognize and far too many hands. Its face is a series of concentric circles like the rings of a tree.

There are fewer workers in the house now. The sound of hammering and chisels on the outer stones has slowed. The house is nearing completion.

The woman is ancient. She sits in front of the clock, mute. Her eyes follow me as I pace the stone floors.

The wizard comes. “It is time.”

The old woman nods. She closes her eyes, leans down upon the metal face of the clock, and breaths a final shuddering sigh.

The clock begins to tick.

I watch the wizard watch her and then carry her body beyond the doors of the house. In a few moments he returns with a long blue gown.

“We will wait upon my brother in his palace this night,” the wizard says. “You will wear th

is.”

I shake my head.

All the workers have gone. We are alone.

“I speak the word of unbinding,” he says gravely, then speaks it. I feel it, prickling like fire up and down my arms. “Your garments will fall to dust.” He pauses for a moment. “I will wait outside.”

I should defy him. I should flee up the stairs or wait, stubborn and naked, for his return. But I am frightened and powerless, and he said we would be visiting the palace, which means leaving the house. I tell myself perhaps there will be opportunity for escape.

The gown is beautiful, finer than any fabric I have seen before.

The clock has moved to the wall. I did not see it move, but now it is there, beside the door, keeping an inscrutable time.

“You are naked, Sylva Sybila.”

I spin, covering myself, but the voice is only that of the clock. It is not the old woman’s voice.

“Who are you?” I demand, angry and ashamed.

“I am the timepiece.”

I shrug into the gown. “Then what time is it?”

“It is the beginning,” it says.

The wizard steps back into his house. It is impossible to read his face, as it always is. He says nothing, makes no apology, but bids me follow. Outside, we find the same skiff waiting that brought me here.

The clouds around the house are roiling. It seems the house—disguised, I now see, with its outer surfaced carved to mirror the whorls and billows of a cloud—rides at the center of a cyclone. For a moment I am terrified to step into the boat, but my anger overcomes my hesitation.

I will find a way to kill the wizard. I try to make the words like steel in my mind, forcing myself to believe them. I will escape to my family’s valley in the mountain.

The wizard watches the clouds as we approach the wall of white. Before, he stood in the prow and spoke a word to part the walls of cloud, but now he says nothing. They part nonetheless, stretching backward like ribbons of steam, ripping away until the whole tent of cloud collapses, opening like a pale flower and falling away.

The house floats behind us in an empty sky.

The wizard’s eyes widen, but he says nothing.

First Fleet #1-4: The Complete Saga

First Fleet #1-4: The Complete Saga Treacherous Beauty

Treacherous Beauty Beneath Ceaseless Skies #166

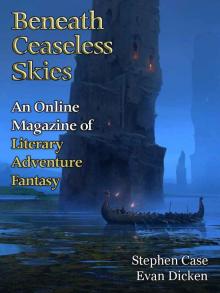

Beneath Ceaseless Skies #166 Beneath Ceaseless Skies #212

Beneath Ceaseless Skies #212 Beneath Ceaseless Skies #231

Beneath Ceaseless Skies #231