- Home

- Stephen Case

Treacherous Beauty

Treacherous Beauty Read online

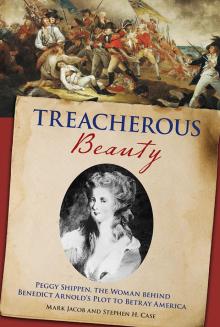

TREACHEROUS BEAUTY

Peggy Shippen, the Woman behind Benedict Arnold’s Plot to Betray America

MARK JACOB AND STEPHEN H. CASE

LYONS PRESS

Guilford, Connecticut

An imprint of Globe Pequot Press

Copyright © 2012 by Stephen H. Case

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, PO Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

Layout: Joanna Beyer

Project editor: Ellen Urban

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jacob, Mark.

Treacherous beauty : Peggy Shippen, the woman behind Benedict Arnold’s

plot to betray America / Mark Jacob and Stephen H. Case.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

E-ISBN 978-1-4930-0010-4

1. Arnold, Margaret Shippen, 1760-1804. 2. Arnold, Benedict,

1741-1801. 3. American loyalists—Biography. 4. United

States—History—Revolution, 1775-1783. I. Case, Stephen H. II. Title.

E278.A72J34 2012

973.3’85092—dc23

[B]

2012012815

Dedicated to Stephen’s grandchildren—Paul Anguel Case, Charles Edmonds, Samuel Case, Kathryn Edmonds, Theron Case, Archer Case, and Benjamin Ayres—and Mark’s grandparents, Marian and Gerald Witham and Helen and C. L. Jacob.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Preface

CHAPTER 1: Princess of Philadelphia

CHAPTER 2: No Safe Haven

CHAPTER 3: Enter André

CHAPTER 4: The Meschianza

CHAPTER 5: Arnold Arrives

CHAPTER 6: Love and Money

CHAPTER 7: The General’s Wife

CHAPTER 8: Spymaster

CHAPTER 9: The Dance of Deceit

CHAPTER 10: The Way to West Point

CHAPTER 11: “The Greatest Treasure You Have”

CHAPTER 12: Meeting after Midnight

CHAPTER 13: A Capture and an Escape

CHAPTER 14: The Mad Scene

CHAPTER 15: Pariah of Philadelphia

CHAPTER 16: The Three Fates

CHAPTER 17: “The Handsomest Woman in England”

CHAPTER 18: Strangers in America

CHAPTER 19: Unmanned

CHAPTER 20: The Keepsake

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Chapter Notes

Bibliography

About the Authors

Index

Preface

When histories of the American Revolution were first written, Peggy Shippen was a mere footnote, if she was mentioned at all. The lovely young lady from Philadelphia had married a man twice her age, General Benedict Arnold, before he conspired to deliver the strategically vital forts at West Point, New York, to the British and perhaps arrange the capture of his supreme commander, George Washington. Peggy Shippen was pitied as the unfortunate, innocent wife of a traitor.

More than a century later, her story took a dramatic turn. The papers of British general Henry Clinton, acquired in the 1920s and donated to the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan, implicated Peggy as a key player in the turncoat negotiations between her husband and the British.

By that time, however, there was a lot of history to undo, and Peggy never got the attention she deserved.

This is the first nonfiction book to focus on Peggy’s life, rather than depict her as a supporting character in her husband’s story or as a subject of historical fiction. It is intended as a popular biography that brings a fascinating yet little known American story to a wider audience. While our narrative and interpretation are original, they rely on the work of renowned historians, among them Carl Van Doren, James Thomas Flexner, Clare Brandt, Robert McConnell Hatch, and Willard Sterne Randall. We also refer to rarely studied letters from Peggy to her son Edward that were provided to us by her descendant Hugh Arnold.

In writing for a general audience, we have edited some quotations to eliminate distracting quirks of punctuation, old-fashioned spellings, and the jarring capitalization style of the era. While presenting Peggy’s lushly romantic tale, we have taken great pains to rely on solid information and to exclude accounts that appear unreliable. We have been helped immensely in our quest by academic researchers Andrea Meyer, Stephanie Schmeling, Julianna Monjeau, and Marie Elizabeth Stango.

The Clinton papers document Peggy’s involvement, but many details remain unknown, and Peggy was never confronted with the facts and compelled to explain her actions. Even today, some people question her complicity despite the evidence. We hope that the reader will not consider it a repudiation of the Bill of Rights and the concept of “innocent until proven guilty” if we issue our own extralegal verdict: Peggy Shippen was guilty . . . and she was fascinating, too.

CHAPTER 1

Princess of Philadelphia

On an early autumn morning in 1780, a lovely young woman named Peggy Shippen seemed to go stark raving mad.

Her husband, a hero of the American Revolution named Benedict Arnold, had just fled to the enemy, abandoning her in a tidy country estate in New York’s Hudson Highlands. Left alone to answer for the treason, she screamed and wailed and shrieked, her cries of anguish reverberating throughout the house. Half dressed in the presence of proper men, she clutched her infant son to her breast and gave voice to fevered hallucinations. She declared that her husband had risen through the ceiling, and that hot irons had been put into his head. The hot irons were torturing her, too, and only the commander in chief, George Washington, had the power to take them away.

But when Washington arrived in her bedroom to comfort her, she declared him an impostor who was planning to murder her child. And she wept, and she wept some more.

Washington and other men of honor vouched for her innocence and virtually worshiped at her bedside. And so a woman whose espionage and treachery brought the new nation to the brink of disaster was allowed to go free, vilified by a few but pitied and admired by many more.

She was only twenty years old, and she had fooled the Founding Fathers. This is the story of how Peggy Shippen arrived at this mad scene, and how she found a way to overcome it.

On June 11, 1760, a prominent Philadelphia lawyer named Edward Shippen wrote a letter to his father, leading with the news that a debtor was willing to pay up—if only his father would send the vouchers before the man left for England. The second most important item of business was personal: Shippen had received “a present of a fine baby, which though of the worst sex, is yet entirely welcome.”1

The “worst sex” was female, and the baby was given her mother’s name, Margaret, along with her nickname, Peggy.

She was born with brilliant prospects. In a new country, she was from old money. She was the descendant of not one but two mayors of Philadelphia, and was the granddaughter of one of Princeton University’s founding trustees.2 She joined a family that was filled with affluent skeptics, well-educated, modern, and somewhat quirky people who were part of Philadelphia’s

power structure but didn’t always run with the pack.

The Shippens had three daughters, then a son, then Peggy. Two more sons followed Peggy, but neither lived beyond age three, leaving Peggy as the baby of the family. Because the single surviving son was a disappointment to his parents, Peggy was treated as the star, the offspring with the greatest potential, despite the perceived handicap of being female. Though not deemed worthy of the first paragraph in her father’s letter, Peggy would become his favorite child.

She had blond hair, delicate features, and an endearing manner. Her eyes were variously described as blue, hazel, and gray, but in any case they were bright and flashing, an advertisement for the intelligence that lay behind them.3

People often remarked on her charisma and physical allure. As she grew to adulthood, women would admire her and want to be her friends. Men would describe her as the most beautiful woman in the room, or the most beautiful in the city, or the most beautiful in North America or in all of England. But Peggy was no bauble. She would also impress men on two continents with her sharp-eyed view of the world, her command of social situations, and her savvy in negotiating financial matters.

Peggy was raised like many wealthy children of her time, constantly attended by servants. She had a sense of entitlement but also a sense of obligation, with a mission of education, self-improvement, and family achievement. She had little interest in politics, but it was her misfortune to live at a time when politics was unavoidable. She came of age with the country—turning sixteen less than a month before the Declaration of Independence was approved in Independence Hall a few blocks from her home.

She grew up on Society Hill, the best neighborhood in a bustling, brash city. Over the three decades that preceded the Revolutionary War, Philadelphia’s population more than tripled, from thirteen thousand to forty thousand, making it the most populous city in North America and one of the most populous in the English-speaking world.4

The Shippen mansion on Fourth Street near Prune (now Locust) sat amid tall pines. It was four stories high, forty-two feet wide, and about the same depth. The facade was made of red and black bricks, with the long and short sides of the bricks alternated in the style known as Flemish bond, which was favored by the affluent.5 A formal garden and orchard graced the property. The interior featured fine furniture, an excellent library, and another common property of the wealthy: African slaves.

There was no indication that the Shippens struggled with their consciences over slavery, as some colonists were beginning to do. Indeed, a 1790 letter by Peggy’s father offered to sell his slave Will for half of the one hundred pounds he had paid for him. Peggy’s father described Will as “tolerably honest” but complained that he was “rather an eye servant,” meaning that he worked only under the watchful eye of his master.6

The Shippen family was Quaker when it settled in Philadelphia four generations earlier, but had embraced the Church of England by the time Peggy was born. She was baptized at Christ Church, a center of worship that was founded in 1695 and is spreading the Episcopal message even today.7

A high point for the church came six years before Peggy’s birth with the construction of a steeple and installation of eight bells weighing a total of eight thousand pounds. The initial bell-ringing marked the funeral of Pennsylvania governor Anthony Palmer’s wife, who was said to have been the mother of twenty-one children and to have lost all twenty-one to tuberculosis, then known as consumption.8

While the first ringing of Christ Church’s bells marked one death, it caused another. An early history reported that a bell ringer was fatally crushed because of his “ignorance and ill-judged management of the bell rope.”9

Colonial Philadelphia was full of risks and rewards. Indeed the city’s growth was built on gambling—Christ Church’s steeple was financed by lotteries, as was the paving of roads.

In an era when ship travel was supreme, the city’s location upriver from Delaware Bay made it a great center of commerce. By the time of the American Revolution, more than five hundred hatters were counted in Philadelphia alone.10 Wealthy families like the Shippens sipped imported Madeira and French wines and dined on turtles shipped live from Jamaica.11

The markets were meccas for both the rich and the working class. All ears could hear the peal of Christ Church’s bells on Tuesday and Friday nights, announcing that markets would be open the next morning. Farmers brought the predictable staples, of course, but also sold frogs that they caught in their ponds. At market, a lady’s social standing might be signaled by whether a maid trailed behind her with basket in hand or she carried the basket herself. When buying butter, it was customary to take a taste first, and the sellers set up small pyramids of butter for that purpose, providing a spoon or a fork. Prominent men of Philadelphia eschewed the common utensils, using their own coins to scoop tastes of butter.12

Peggy’s Philadelphia was as cosmopolitan as the colonies could be, with strong religious foundations but a measure of tolerance and acceptance of diversity that was far from universal in America. Pennsylvanians were “a people free from the extremes both of vice and virtue,” as Thomas Jefferson put it.13

Even before Peggy began to make history, she was surrounded by it.

Philadelphia’s role as both a destination and a crossroads allowed her father to play host to the most accomplished and influential visitors of his day. During Peggy’s childhood, houseguests included George Washington, the wealthy Virginian who would later become the Father of His Country, and Benedict Arnold, the audacious military officer who would later become Peggy’s husband—and his nation’s most famous traitor.14

Another transformative figure in American history, Benjamin Franklin, was a friend of both of Peggy’s grandfathers. By the time Peggy was born, Franklin’s famous electricity experiment with a kite and a key was eight years old, and Franklin was often gone from Philadelphia on long diplomatic trips to London.15

Among the visitors to Philadelphia when Peggy was three years old were a pair of English surveyors named Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, who were hired to establish the Maryland-Pennsylvania border, later known as the Mason-Dixon Line, one of the most famous borders in American history.16

Indeed, Peggy was in the company of greatness from the very start.

A Philadelphian born the same year as Peggy—but of far lower caste—was Richard Allen, a slave who gained his freedom and became the leading founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Allen’s owner was Benjamin Chew, the chief justice of Pennsylvania, whose daughter was one of Peggy’s childhood friends.17

When Peggy was a child, her father’s cousin Dr. William Shippen caused an uproar in Philadelphia by using cadavers in medical education and advocating the involvement of men in midwifery. Rocks were thrown through his windows, and charges abounded that he was a grave robber.18 But his efforts advanced medicine, especially in the battle against infant mortality, which was ten to twenty times higher in the American colonies than it is in the United States today.19 (Dr. Shippen’s father, William, also a physician, famously assessed his profession by saying, “Nature does a great deal, and the grave covers up our mistakes.”)20

There was yet another noteworthy person in Peggy’s vicinity—Elizabeth Griscom, who was eight years old and lived about three blocks away when Peggy was born. Griscom, whose married name was Betsy Ross, served the needs of American mythmaking and is remembered, accurately or not, as the woman who made the first American flag.21 Today Betsy Ross is far more famous than Peggy Shippen, though far less significant in the events of her time. But she fit the stereotype better: Women were meant to sew flags, not to sow conspiracies.

The Reverend Andrew Burnaby, a British travel writer who visited Philadelphia around the time of Peggy’s birth, said, “The women are exceedingly handsome and polite. They are naturally sprightly and fond of pleasure, and, upon the whole, are much more accomplished and agreeable than the men.�

��22

But the men were in charge, and always had been.

Two of the most accomplished patriarchs among Peggy’s Shippen ancestors—her grandfather and great-great-grandfather—showed a special ambition and intelligence, like hers. And also like Peggy, they were tortured by the harsh judgments of society.

Peggy’s great-great-grandfather, the first Shippen to cross the Atlantic from England to America, was Edward Shippen, son of an overseer of highways in Yorkshire. By 1668, when Edward was about thirty years old, he had arrived in Massachusetts and set up as a merchant, leasing dock space in Boston and developing trade with the Caribbean, then typically called the West Indies.

Edward soon married a Quaker woman and shed his Anglican roots to join her faith. It was not a popular move; it separated him from the majority of Bostonians and invited persecution.23 The Quakers—formally the Society of Friends—were known for their pacifism, their rejection of social distinctions, and their refusal to swear allegiance to government.24 In 1677 Edward Shippen was arrested twice and subjected to public whippings for the crime of attending Quaker meetings.

Edward nonetheless found business success in Boston. His family thrived, too, with his wife bearing eight children in seventeen years before her death in 1688. Shippen remarried and, in 1694 at the age of fifty-five, resettled in Philadelphia. The reasons for the move are in dispute. According to some historians, a meteor over Boston prompted superstitious Puritans to launch a new wave of persecution against Baptists and Quakers. But others insist that no such pogrom occurred.25

In any case, Edward’s Quaker beliefs were far more welcome in Pennsylvania, a province founded by a Quaker, William Penn. Also very welcome was Edward’s wealth. When he arrived, he may have been the wealthiest man in the Philadelphia area.

Edward was immediately invited into the government and served as the city’s first mayor. He acquired hundreds of acres of property, rode in a fine carriage, had his portrait painted, and lived in a mansion overlooking the city and the Delaware River. His Second Street estate, later known as Governor’s House, featured orchards, gardens, and herds of deer.26 When William Penn visited Pennsylvania, Shippen turned over his mansion as temporary home for the province’s “absolute proprietor.”27

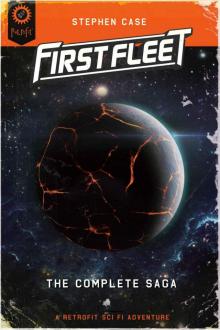

First Fleet #1-4: The Complete Saga

First Fleet #1-4: The Complete Saga Treacherous Beauty

Treacherous Beauty Beneath Ceaseless Skies #166

Beneath Ceaseless Skies #166 Beneath Ceaseless Skies #212

Beneath Ceaseless Skies #212 Beneath Ceaseless Skies #231

Beneath Ceaseless Skies #231